I found a yellowed newspaper

clipping tucked away in a seldom-disturbed file. The partial editorial was

written August 1, 1976, after the Montreal Olympics. The unknown writer’s

comments can still bring tears to my eyes.

Olga Korbut of the USSR had been the

darling of the 1972 Olympics. Now younger girls outshone her, and she looked

lost and lonely. Then she won a silver medal in her final event, and “the crowd

stood up and screamed its acclaim.… They were there for Olga Korbut when she

needed it most ― and it was good to see.”

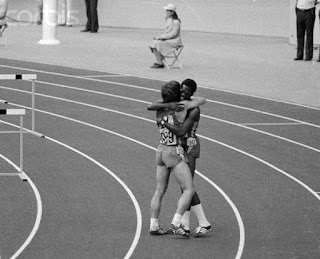

One other incident stood out for

the writer. A young black American, Edwin Moses, won the hurdles and set a

world record. “But there were records everywhere. It would have passed and

nobody would have really cared very much.” But an unknown American named Mike

Shine, who won the silver second, could not contain his joy. He raced over to

Moses and hugged him. Moses hugged him back.

“And the crowd saw it, too. And

they went slightly insane.

“And when the two young men ― one

black, one white ― circled that track grinning and waving and swept up in the

incredible wonder of the moment ― that mob from a score of countries stood and

screamed for minutes.”

There may be a lot wrong in the

world, but there is also a lot right.