One of the lesser known incidents

of World War II occurred during the week of the Pearl Harbor attack on Sunday, December

7, 1941.

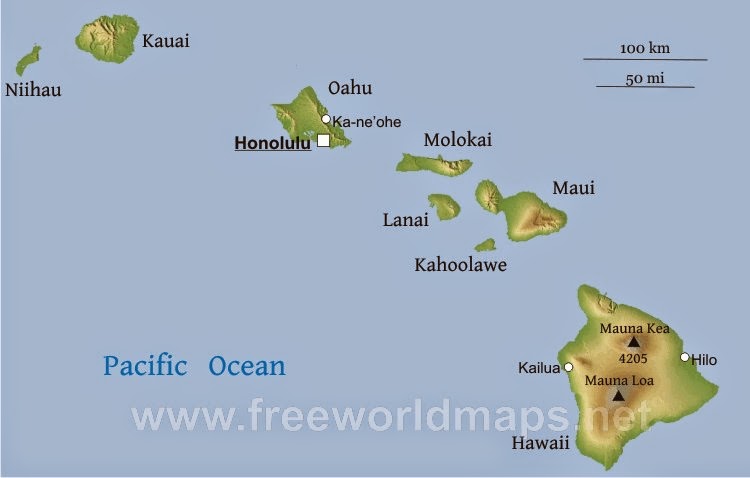

In their briefing before they

attacked the American naval base, Japanese pilots were told to head for the

westernmost Hawaiian Island, Niihau, if they had airplane trouble. A submarine

assigned to rescue duty would pick them up.

Twenty-two year old Zero fighter

pilot Shigenori Nishikaichi flew escort of a flight of bombers during the

attack. During an aerial dogfight with a flight of obsolete Curtiss P-36A

fighters, Nishikaichi’s gas tank was punctured. He wouldn’t make it make to his

carrier, the Hiryu. Niihau lay 130

miles to the west. Along with another damaged Zero, he headed for the island.

When they reached the eighteen-mile-long,

six-mile-wide island, they discovered Japanese intelligence was wrong. The

island of Niihau, owned by the Robinson family since 1864, was home to 136

residents, mostly native Hawaiians whose primary language was Hawaiian.

Unsure what to do, they turned

away. The other pilot suddenly dove into the sea. Nishikaichi headed back to

the island and made a rough landing in a pasture near a lone house. The plane’s

wheel hit a fence, causing the plane to nose in. His safety harness broke free

and Nishikaichi slammed into the instrument panel.

The home’s occupant, Howard

Kaleohano, pulled the pilot out of his plane, along with his gun and

official-looking papers. He took him to his house, where his wife served him

breakfast. Since Nishikaichi spoke limited English, the Kaleohanos summoned

60-year-old Ishimatsu Shintani, who was born in Japan but had lived in Hawaii

for over forty years.

Shintani was reluctant to get

involved. After a brief conversation with the pilot, he looked shocked and left

without telling the Kaleohanos what was said.

Next they

brought Yoshio and Irene Harada, Japanese Americans whom the Niihauans

considered more Japanese than Hawaiian. Nishikaichi informed them of the attack

on Pearl, but the Haradas did not relay that crucial information to their

neighbors.

The rescue

sub never came; it had been ordered to proceed toward Oahu in the early

afternoon.

Niihau had

no electricity or telephones. Unaware of the attack, the islanders held a luau

for the pilot. That night, the islanders heard a report of the attack on a

battery-operated radio.

The next

morning, they took Nishikaichi to the dock where Aylmer Robinson was expected

to arrive for his weekly visit. Unknown to them, in the wake of the Pearl

Harbor attack, all boat traffic had been banned in the channel between Niihau

and Kauai, where Robinson lived. Robinson didn’t come.

While they

waited, Nishikaichi and Harada spoke privately. The pilot told Harada that

Japan would surely win the war if Pearl’s lack of defense was any indication.

He lured Harada into treason.

|

| A stone column was erected in Shigenori Nishikaichi’s honor in his hometown in Japan. He died in battle over Oahu, claims the inscription. “His meritorious deed will live forever.” |

By Thursday,

they’d gotten Shintani involved. They sent him to the home of Howard Kaleohano

to demand the return of Nishikaichi’s documents, which the pilot had been told

should not fall into American possession. Kaleohano refused to return them.

Harada stole

a pistol and a shotgun from the Robinson’s unused ranch house. He and the pilot

overpowered the Niihauan guard assigned to watch Nishikaichi while Irene Harada

played a phonograph record to drown any sounds of struggle.

Harada and

Nishikaichi went to Kaleohano’s house for the papers. When they didn’t find him

at home, they went to the crashed plane, apparently to try to use its radio.

They forced the 16-year-old guarding the plane to accompany them back to

Kaleohano’s house. This time they found him there. Harada fired at him, but

missed. Kaleohano escaped, and warned the islanders before heading to the

northern tip of the island to build a signal fire.

The

overpowered guard escaped from the warehouse he’d been locked in, and added his

own warning. The Niihauans scattered to remote parts of the island.

That night,

Kaleohano and five other men rowed against the wind on a ten-hour journey to

Kauai. With Kaleohano’s report, Aylmer Robinson was finally allowed to mount a

rescue mission. It would arrive too late.

Meanwhile,

Nishikaichi and Harada captured Kaahakila Kalima, whom Harada sent to inform

his wife that he would not be returning home that night. Nishikaichi and Harada

walked through the deserted village, firing their weapons and yelling for

Kaleohano.

After

delivering the message, Kalima had joined his wife and Ben and Ella Kanahele on

the beach. When the men went back to the village looking for food, they were

captured by the enemy duo. After searching Kaleohano’s house for Nishikaichi’s

papers to no avail, they burned the house down. They forced Ben Kanahele, a

powerful, six-foot, forty-nine-year-old, to find Kaleohano. Ben knew Howard had

gone to Kauai, but pretended to search.

Nishikaichi

threatened to murder all the islanders if Kaleohano wasn’t found. Ben demanded

in Hawaiian that Harada take away Nishikaichi’s pistol. Harada refused, but

asked the pilot for the shotgun.

By this

time, Friday night, Nishikaichi was exhausted. As he handed the shotgun to

Harada, Ben lunged for him. Nishikaichi managed to pull his pistol from his

boot and shot Ben in the chest, groin, and hip. Undaunted, Ben grabbed him and

threw him against a stone wall. Ella bashed his head with a rock. Ben then slit

Nishikaichi’s throat with a knife.

Harada

rammed the shotgun into his mouth and killed himself. The hostile takeover

ended.

Ben Kanahehe

recovered from his wounds and received the Medal of Merit and the Purple Heart.

His wife received no official recognition. Ishimatsu Shintani spent the war

years interned on the mainland. Irene Harada was imprisoned until late 1944.

|

| Benehakaka (Ben) Kanahele holds his Medal of Merit and Purple Heart. |

The actions

of the three Japanese Hawaiians, according to a Navy report in January, 1942,

indicated “the likelihood that Japanese residents previously believed loyal to

the United States may aid Japan.” There’s a good chance the Niihau incident

helped persuade the government to intern over 100,000 people with Japanese

ancestry away from the West Coast.

For further reading:

For further reading: